Amusing Workshop Experience That Created My Future

The morning after I graduated from Westminster Choir College in May 1968, without telling family or friends, I enlisted in the army. 1968 was an intense period of the Vietnam War, but I did not enlist because I believed in war. On the contrary, I felt it unworthy to accept the benefits of our country without stepping up and doing my part. I was the only one in my unit who had enlisted instead of being drafted. In order to prepare myself for what I knew would be physically intense basic training, I preceded my army entrance by working hard labor for three months in Oklahoma. Then, a week before my army time began, I went with my folks to a Choristers Guild church music workshop in Naramata, British Columbia.

Dad, as the Choristers Guild Executive Director, was both administrator and the adult choir clinician for that week, and Mom, of course, was the Children’s Choir clinician. I joined them as a guest to say goodbye. I had no responsibility and found myself just sitting around…but I quickly noticed that there were lots of idle youth sitting around too. The workshop involved adult and children’s choirs, but there was no activity for youth in those days.

A fun idea popped into my head. I surreptitiously began talking to these idle kids, passing the word that we might be able to come up with something that would blow the minds of the adults. The bored kids loved that idea. The youth and I agreed to meet in secret every evening that week. I taught them to sing, and we learned a rousing and spirited Jamaican anthem called Calypso Noel. Some of the youth played flutes, guitars, and percussion, so we added to the fun! None of the adults at the workshop had any idea that this was happening.

On Friday, at the end of the workshop week, Dad had just started his final adult rehearsal…when I walked in quietly and tapped him on the shoulder. I said that some youth had come to me and asked if they could sing a little something to the adults. I told Dad it would mean a lot to them, so would he allow that to happen? Being an efficient choir director, Dad was conflicted, but he finally allowed them to sing. With a smile, I then turned around and snapped my fingers…and in marched 70 youth, dressed to the hilt and bursting with spirit and enthusiasm. They sang the memorized music with phenomenal spirit and they knocked the adults crazy! Afterwards, the adults just kept on clapping, insisting that the youth sing it again, which they did!

That happening was just meant to be a smile enhancing surprise, but it ended up changing of the style of the Naramata Summer School. At every annual summer music school in Naramata since then, a youth choir has always been included!

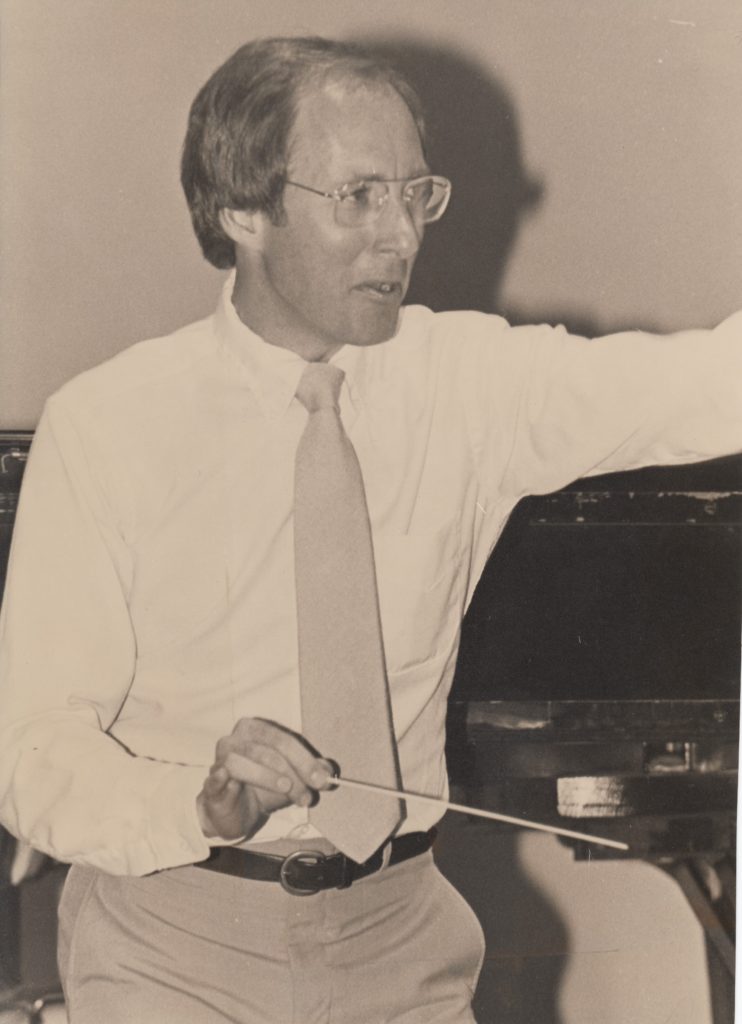

But this happening changed more than that. The morning after the closing concert of the workshop, as our family was getting ready to depart, the administrator of the summer school pulled me aside and asked how long I would be in the army. I told him probably two years. He then said, with determination, “On the summer after the army, would you be willing to come back to Naramata and be our official youth choir clinician?” Two years later, that actually happened, my first choral workshop at age 24, which opened the door to what would eventually grow to 526 workshops throughout the US, Canada, and other countries. Naramata bought me back as youth choir clinician 6 times and as adult choir clinician 5 more times. Here are reviews of my life of conducting and workshops, all of which happened because of that fun, pre-army experience in Naramata.

Post-Workshop Personal Letter

Dear Michael, well, you’ve done it again. You’ve moved me to tears. But before you think it’s all your fault, let me assure you that “MUSIC” always makes me cry (or laugh as the case may be); but not just cold clinical music. First it has to be taken in and cuddled a bit and warmed up in somebody’s soul; then it has to be shaped a bit, wrapped up in appropriate trappings and introduced in a sympathetic atmosphere by someone who really loves and understands it. Damn it all, that’s just what you do. You see, it is not you at all, it’s the music in your soul. And I swear if you hadn’t been blessed with the ability to get it out, you would explode or you’d blow yourself up (whichever was the first to occur).

But let’s go right on the next step…the one that lets you accept whatever we offer, as long as you consider it a sincere effort. Then you inspire us to do better, and we do! BUT!!! If we don’t, that great safety valve, your sense of humor, opens up to let the pressure off, and we go back for a second try. Watching you direct our little band of crows trying to sing like meadowlarks and sounding like cuckoos, really made me swell with pride to think that I was lucky enough to know you as a friend, not just a conductor. Sincerely, Bud Buchan (a Canadian church choir member)

Further Reviews

“It is difficult to express how excited everyone was with your conference here at Furman University as this year’s guest scholar. I heard nothing but glowing remarks about your lectures, your attitude, your enthusiasm, and the vigor and understanding with which you worked. Thank you for presenting one of the finest choral conferences here ever. Congratulations!” Dr. Bingham Vick, Jr., Furman University, Greenville, South Carolina

“It has been a special pleasure to teach alongside you, Michael. You have such joy, such verve, such humor in your presentations. No wonder everyone loves you, as we do, and enjoys being with you. You have a special gift, to be certain. It was a privilege being with you.” Dr. Weston Noble, Luther College, internationally famous conductor

“Fantastic…two thumbs up…outstanding director…meticulous rehearsals…the quality of instruction was wonderful…the energy of the conductor was infectious! The youth were inspired and enriched by working under your direction, and came away with a feeling of a job well done. Thank you for all your energy and enthusiasm, for imparting your knowledge and obvious love of what you are doing to them, for challenging them to reach high.” Agnus French, Lancaster, PA, American Guild of Organists

Reviews From Germantown Academy

“Michael Kemp is remarkable in every way. Arriving at the school when our choral program was dwindling due to lack of leadership, Michael turned the situation around in one year, taking a choir of twelve lackluster singers to a choir of 75 enthusiastic singers, who grew exponentially in their skills as musicians and singers in the course of that year. Simultaneously, Michael started an adult choir, the Academy Chorale, growing in one year to over 80 singers. He also founded the Academy Chamber Society, an orchestra which grew in that same year to 45 semi-professional musicians from all over Philadelphia. I have sung in the Academy Chorale and watched rehearsals with students, knowing first hand that his rehearsals and subsequent performances are both masterpieces of serious purpose, affirmation, and humor. Each rehearsal is a voice lesson, a music theory lesson, and another step in one’s own and the group’s growth. Michael seems to know just the right way to motivate, to demonstrate, to instruct, to get the best musicianship everyone can give.” Suzanne Perot, Assistant Head of School

“Michael, the combination of energy and expertise you have brought to the school has been breathtakingly positive for Germantown Academy in terms of singing, spirit, community building, and outreach. The stereotype of a person as charismatic as you includes a healthy disdain for “sweating the small stuff”, so we find your painstaking attention to details, whether they be related to a performance, a gala Caribbean choir tour, or an advisee in need, very heartening.” Anthony Garvan, Head of Upper School

“Sunday’s performance was spectacular, but that is the standard the GA community has come to expect from the adult community ensembles, Academy Chorale and Orchestra, which you created. Witnessing the joyful expressions on the faces of those who practice such sophisticated musical arts lifts the spirits of all who attend. My thanks, Michael, for the many gifts embedded in each performance: the gift of great music, the gift of transferred joy, the gift of community within community, a circle within a circle.” Jim Connor, Head of School

Comments From Academy Chorale & Orchestra Members

“I was excited to find in you a leader with proven knowledge and experience, and inexhaustible energy and enthusiasm, but also a unique ability to convey to singers what the music really meant, as well as a vision of what the performance was designed to convey to the audience. While leading every rehearsal, you consistently displayed gentle good humor, unfailing patience, and a clear understanding that the performers were there to have fun too! In a society so divided, you have convinced us that music unites us, sharing the beauty and joy of music. Michael Kemp…YOU have truly inspired us!”

“Your passion for the music is contagious and, no doubt, is the reason why we are all inspired to perform to our personal best. Thank you for never tiring of trying to take every piece of music beyond correct notes and rhythms as you attempt to stay true to the composer’s vision, ultimately creating an experience that is meaningful to the musicians as well as the audience.”

“There were numerous concerts which we sang with you with emotionally tear-filled eyes. How can there be so much unheard beauty lying dormant on a piece of paper? Michael, we are forever thankful for your talent of changing this piece of paper to a beautiful, heart-wrenching movement of true music.”